Sunday, October 31, 2021

Wednesday, June 16, 2021

Woodcuts and Witches - The Public Domain Review

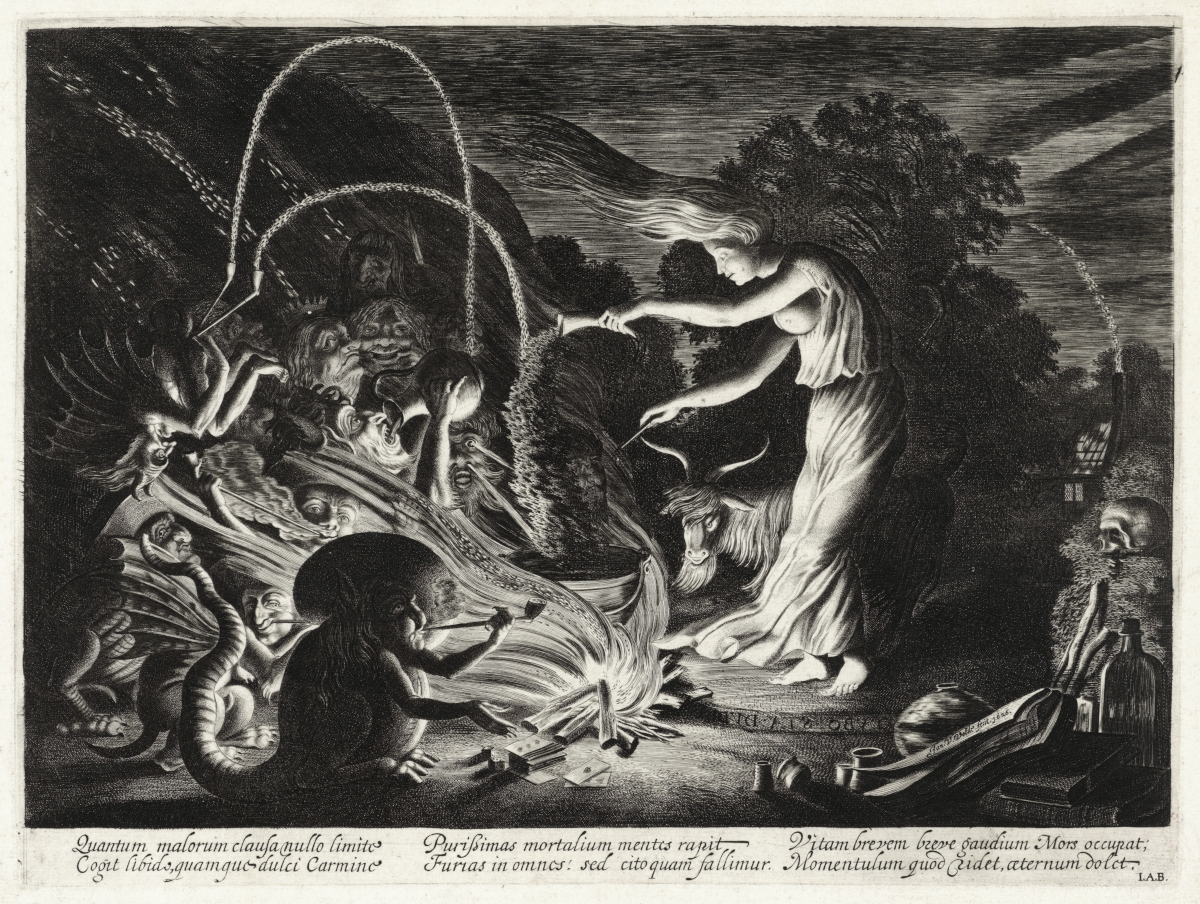

The Public Domain Review is an excellent source of obscure illustrations and related esoteric essays. Where else can you learn about Pre-Raphaelite wombat obsessions? Wombats aside, collections and essays include much for aficionados of horror and fantasy. The "Ghosts and Occult" collection ranges from this 17th century engraving to 19th century magician's manuals to some very strange Persian demons from the 1920s.

| ||

| The Sorceress by Jan van de Velde II (1626) |

|

| 16th century occultist Edward Kelley raises the dead. |

| |

| Neither demon face seems to be enjoying this... |

Whether horror or not, there are some incredible and very unusual collections here.

Friday, April 30, 2021

Ivan Bilibin's Baba Yaga

|

| Bilibin's cover for Russian Fairy Tales |

Ivan Bilibin was a stage designer and illustrator whose influences included traditional Russian/Rus' and Japanese art. He gained prominence with his illustrations of folktales collected by Alexander Afanasyev in Russian Fairy Tales (1899). Great stories, great illustrations. Among the best is Vasilisa the Beautiful, which is one of several in the collection featuring Baba Yaga.

|

| Looking grim... |

In an attempt to get rid of her, Vasilisa is sent by her stepmother/stepsisters to Baba Yaga, who sets her up with a series of seemingly impossible tasks. Can Vasilisa survive?

|

| Skull lanterns! |

More of Bilibin's art can be found here.

|

| A detail from the cover. |

Tuesday, April 20, 2021

The 5th Fontana Book of Great Ghost Stories

|

| A very long sermon... |

The price of The 5th Fontana Book of Great Ghost Stories (first published in 1969) hasn’t gone down on Amazon since I first mentioned it, so if you have a spare copy in your attic you can sell it (or at least list it) for hundreds. I don’t, so thank you to OP for providing a digital copy.

In this 5th volume, Aickman is still in charge of the selection, and while he devotes little space to discussing the individual stories, he is still pontificating on “the ghost story” in his introduction, despite a promise not to:

“At its best, its true affinity is… with poetry: it is a projection and symbolisation of thoughts and feelings experienced by most people (perhaps by all) but of their nature excluded from the common plod of ordinary prose narrative and record.

We badly need more living writers of ghost stories with the right kind of imagination and a respect for the power and poetry…”

As usual, Aickman’s definition of a ghost story is a loose one – actual specters are the exception here, if indeed there are any at all.

The collection begins with “The Firmin Child” (1965), by Richard Blum, which deftly exploits parental sins and worries – and young Tommy gives his parents much to worry about:

“The spoon, the dances, the silences, the spells. It’s not human. He’s like a devil sometimes, or an animal.”

Tautly written and memorable, “The Firmin Child” is one of the highlights of this volume.

“Lord Mount Prospect” (1965), by John Betjeman (UK Poet Laureate from 1972 until his death in 1984), provides the inspiration for the cover illustration. It’s nice that the (apparently uncredited) illustrator actually provided illustrations from the stories for all the Fontana volumes, instead of generic ghosts. The story itself involves a “Society for the Discovery of Obscure Peers”, which discovers a very obscure Irish peer, member of an obscure religious sect, who proves difficult to track down. I found “Lord Mount Prospect” short on poetry, short on plot, and (although Betjeman apparently intended it to be funny) short on humor.

One of the older members of the collection is Mrs. Oliphant’s 1881“The Library Window”. The Scottish Mrs. (Margaret) Oliphant had a long and prolific writing career in which ghost stories played only a small part. This story of a young girl’s obsession with a window across the street which may or may not actually lead to a room is highly enjoyable – cozy but mysterious, and with just enough Scots dialect to add to it rather than detract from it.

Jerome K. Jerome’s “The Dancing Partner” (1893) tells the story of a German maker of mechanical toys who constructs an “electric dancer” for the girls of the town, who aren’t satisfied with their flesh and blood partners. Needless to say, the automaton is debuted a little prematurely. “The Dancing Partner” is short, simple, and satisfying.

Next up is the debut of Aickman’s own “The Swords”, which I first read in Cold Hand in Mine. I’m a big fan of this story, but then again I’m a big fan of most of Aickman’s stories. Here, he really hones in on a very specific type of disquiet and disappointment – the Germans probably have a word for it, but I don’t.

Speaking of Germans, the next entry is “The Mysterious Stranger”(1823), by an anonymous author. Aickman writes that “This German story is the work of an important artist.” The story opens promisingly and atmospherically, as a group of travelers in the Carpathians are menaced by the howling of both “Boreas, that fearful north-west wind” and “reed-wolves” which, it is said, tend to become more rambunctious when Boreas howls.

“The Mysterious Stranger” delights with its Gothic ruined castles in the moonlight, rampaging wolf packs, coffin-filled vaults, and a mysterious stranger who somehow controls the wolves and exerts a malign influence on the bold Franziska. It must have occupied a prominent place on Bram Stoker’s bookshelf.

In Elizabeth Walter’s “A Question of Time” (1969), an old picture of “a monk, sort of greyish, with long pink fingers”, turns out to portray a Father Furnivall, who was tortured to death in the 17th century. The picture causes a strange reaction in the young man who buys it, causing him to imagine that he was there for the torture – or is it his imagination? Unfortunately, “A Question of Time” fails to build to anything particularly gripping.

Maurice Baring’s “Venus” (1909) involves a man who, seeing an advertisement for Venus Soap in a telephone box, begins to be transported to, or imagine himself transported to, the jungle-shrouded conception of that planet. Like “A Question of Time”, there isn’t enough development in this story to make it particularly memorable.

It’s always refreshing to see a W.W. Jacobs story that isn’t “The Monkey’s Paw” in an anthology. “Jerry Bundler” (1897) begins in a cozy inn where “three ghost stories… had fallen flat” (coincidentally the same number which fall flat in “The 5th Fontana Book of Great Ghost Stories”). The fourth is more of a success, since it involves a murder-minded ghost said to haunt the very inn in which the stories are being told. It may, in fact, end up being too successful…

The collection ends with the scintillating “The Great Return” (1915) by Arthur Machen. Mysterious events are occurring in Llantrisant, on the coast of Wales, and the narrator goes to investigate, to be promptly told by the local rector that “You are not worthy of this mystery that has been done here.” Has a new religious sect sprung up, or is the change in the town due to something much older?

So, the 5th Fontana Book of Great Ghost Stories contains a diverse group of stories, and some are excellent.

Sunday, March 21, 2021

All about Aickman: The Tartarus Press Aickman Page

Tartarus Press, a British publisher of supernatural fiction, has a page devoted to Robert Aickman. It's a great resource for Aickman fans. For me, one of the most useful things was a list of Aickman's stories, along with when and where they appeared in print. Based on that, there are a few that have only been published by Tartarus Press.

There's also a concise Aickman biography, and a link to a much longer documentary on the man and his works:

Sunday, March 14, 2021

Cold Hand in Mine: Strange Stories by Robert Aickman

Strange stories indeed. The subtitle, Edward Gorey’s enigmatic cover illustration, and the opening quote (“In the end it is the mystery that lasts and not the explanation.”) all serve to give the reader a preview of Aickman’s opaque, haunting style. Rarely is there overt horror; instead, a subtle sense of lasting disquiet and dread. As Fritz Leiber put it, Aickman “has a gift for depicting the eerie areas of inner space, the churning storms and silent overcasts that engulf the minds of lonely and alienated people.” The eight stories in this collection provide a great introduction to Aickman’s own areas of inner space.

“The Swords” – A virginal narrator, a disreputable carnival in Wolverhampton, a mysterious performer called Madonna, who is perhaps a distant relative of Olympia from E.T.A. Hoffmann’s “The Sandman”. There’s a great sense of unease and disappointment in this one.

“The Real Road to the Church”, or, perhaps, to the churchyard, since Aickman seems to be referencing corpse roads, the traditional paths on which coffins were carried and on which the spirits of the dead were also said to travel, “until their souls were purged”. In this tale, the unfulfilled Rosa has moved to a house on a Channel island, which, as she comes to learn, is the spot where the corpse porters are changed. This story is especially dreamlike, and less especially disturbing than many of Aickman’s works.

In “Niemandswasser”, young Prince Elmo and his friend Viktor fall under the mysterious influence of a lady (or something) in a lake. Despite some high points, “Niemandswasser” didn’t fully immerse me.

“Pages from a Young Girl’s Journal” is a rarity for Aickman in that it has an identifiable monster – although the story is about the girl, not the vampire. For more thoughts on this one, see here.

“The Hospice” – I think this was the first Aickman story I read. It is one of the more frequently anthologized ones, probably because, while mysterious, it’s more accessible than most (and it’s a great story). Traveling salesman Maybury runs out of gas in a bad spot, where the only place to go for help is far from ideal.

“The Same Dog” tells the story of a childhood friendship cut short, an eerie house, and an eerier dog. It’s another highlight of the collection.

In “Meeting Mr. Millar”, the narrator tells of a new lodger in the house in which he’s renting rooms. “A haunted man”, Mr. Millar attracts strange visitors, disquieting sounds and stenches.

Finally, “The Clock Watcher” involves the narrator’s German wife, whose growing collection of clocks seems to have a menacing life of its own (“It doesn’t sound like a cuckoo, at all.”). You know it won’t end well, but then again, this being Aickman, it rarely does.

Some weird stories are read once, enjoyed, and forgotten. Aickman’s strange stories are unique, memorable, and so allusive and illusive that they can be returned to again and again.