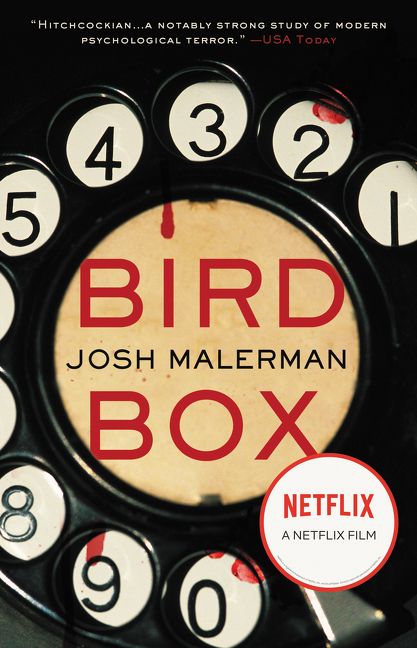

Josh Malerman’s short novel Bird Box was published in 2014. Recently, it’s been adapted as a Netflix film with Sandra Bullock, to be released on December 21. I was attracted to Bird Box by the premise – a mysterious something which cannot be seen without going mad has arrived on Earth, and the survivors must keep the curtains down or wear blindfolds if they go outside.

Wow, I thought, this must be a sort of cosmic Lovecraftian horror. What a great idea, taking out the visuals and relying on the horror of scent, sound, and touch. Imagine protagonists going out in their backyard blindfolded and creeping, terrified, cheek to jowl with Yog-Sothoth. Imagine the chilling, mysterious descriptions of their other senses interpreting “a congeries of iridescent globes” - but how difficult a concept to execute.

Ay, there’s the rub. Malerman often fails to live up to the challenge, providing an example of the familiar caveat for beginning writers: ideas are the easy part, writing is the hard part. Bird Box shows a distinct lack of imagination in terms of describing a world without sight. For example, at one point, the protagonist’s dog is driven mad:

“It sounded like Victor had chewed through his own leg.”

What does this sound like, exactly? Maybe Victor just found a tasty rawhide chew.

Inadequate description aside, I found Malerman’s writing unenjoyable and sometimes irritating (the “tip” of the boat?). The language is plain and simple, often delivered in text message-sized bits. The characters are like the ones in lackluster horror movies who exist only to be picked off, with so little backstory or personality that it’s difficult to separate them into distinct individuals. There’s Malorie (the protagonist), Tom (Malorie’s love interest, although Malerman tells us this but never shows us), Felix, Don, Jules, Cheryl, Olympia (the pregnant one), Victor (the dog), and, of course, Gary (“You’re mad!”). Only “The Boy” and “The Girl”, children born since the apocalypse, inspire any feeling whatsoever.

There is something less than a skeleton of a story here – maybe the stapes or coccyx, the merest forepaw to suggest what might have been. Bird Box focuses more on the claustrophobic horror of being trapped in a house with a bunch of other people than on what’s lurking outside. Incidentally, it’s convenient that the house in which the characters shelter is provided with working phone lines and electricity for years after society has collapsed, not to mention a well in the backyard. There is plenty of canned food available, but sadly no boards to nail over the windows (of course, blankets can be dramatically ripped down when drama is needed).

On the positive side, Malerman does resist the temptation to explain or reveal much about the crazy-inducing creatures which are roaming the world, leaving their true nature ambiguous. The idea that whatever it is might not even have any malign purpose is an appealing one.

I really can’t imagine Bird Box converting to film very well. After all, the whole point is the lack of sight. Watching Sandra Bullock stumble around in a blindfold for two hours sounds vaguely amusing, but completely lacking in chills. Like the novel, it seems unlikely to live up to the premise.